Уйгаруудын дараа Киргизүүд монгол нутаг дээр 50 орчим жил ноёрхон суусан боловч НТ 901 онд киданчуудад шахагдан гарчээ. НТ YI зуунд Ляо голын орчимд нутаглаж байсан Сяньби нараас киданчууд тасарч гарсан гэж судлаачид үздэг. НТ 388 онд киданчууд умард Вэй улсын цэрэгт цохигдон хоёр хэсэгт хуваагдаж баруун зүг шилжин суурьшсан нь Си (күмоси) гэж нэрлэгдэх болсон бөгөөд зүүн зүгт очиж суусныг нь Хятан гэж нэрлэжээ. НТ 901 онд Амбагян хэмээгч Киданы хуучин 8 аймгийг үндэс болгож Хятан улсыг байгуулан хаан суужээ. Хятанчууд хаанаа 3 жил болоод дараагийн хааныг сонгодог байсан бөгөөд эл уламжлал НТ 917 оноос өөрчлөгдөж хаан ширээг үе залгамжилдаг болгожээ.

Уйгаруудын дараа Киргизүүд монгол нутаг дээр 50 орчим жил ноёрхон суусан боловч НТ 901 онд киданчуудад шахагдан гарчээ. НТ YI зуунд Ляо голын орчимд нутаглаж байсан Сяньби нараас киданчууд тасарч гарсан гэж судлаачид үздэг. НТ 388 онд киданчууд умард Вэй улсын цэрэгт цохигдон хоёр хэсэгт хуваагдаж баруун зүг шилжин суурьшсан нь Си (күмоси) гэж нэрлэгдэх болсон бөгөөд зүүн зүгт очиж суусныг нь Хятан гэж нэрлэжээ. НТ 901 онд Амбагян хэмээгч Киданы хуучин 8 аймгийг үндэс болгож Хятан улсыг байгуулан хаан суужээ. Хятанчууд хаанаа 3 жил болоод дараагийн хааныг сонгодог байсан бөгөөд эл уламжлал НТ 917 оноос өөрчлөгдөж хаан ширээг үе залгамжилдаг болгожээ.

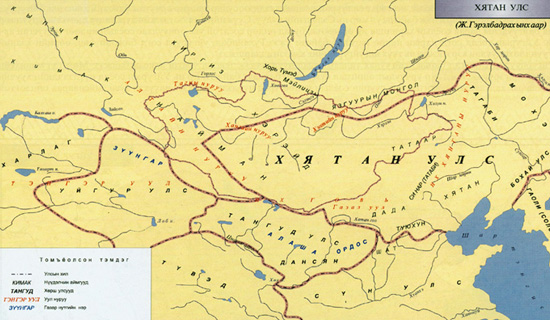

Хятан улс нь 55 аймаг улсаас бүрддэг байсан бөгөөд өмнөд хэсгийн 16, хойд хэсгийн 28, гадаад хэсгийн 8 аймаг, засаг захиргаа төвлөсөн Их аймаг, бага аймаг, хараат аймгуудаас тус тус бүрддэг байв. НТ 951-960 онд Чжоу улстай, 960-1278 онд Сүн, Бохай, Солонгос, Дундад Азийн улсуудтай өргөн харилцааг тогтоож байжээ. Хятан улс нь тус бүр 500-700 морьт цэрэгтэй хүнд, хөнгөн гэж нэрлэгдэх 4 морин цэргийн хороотой байв. Явган цэргийн ангиудаас гадна сайд түшмэд нь хувьдаа цэрэгтэй байжээ. 50 мянган хүнтэй их армийг бүрдүүлж “Улсын цэргийн ерөнхий захирагч” хэмээх цэргийн эрхтнээр захируулж байжээ. Хятан улс галт буу зохион бүтээж дайн байлдаанд хэрэглэсэн бөгөөд ард иргэд нь цэргийн хууль, архи нэрэхтэй холбоотой хууль, давсыг худалдаалах журам бүхий хууль, тамхины хууль, татварын хууль зэргийг дагаж мөрддөг байв.

Алтан улсын хойд хязгаарын 16 хот Хятан улсын мэдэлд байсан бөгөөд Алтан улсын дараа гарч ирсэн Сүн улс нь Ин, Мо, И хэмээх тойргуудад байх тэдгээр хотуудыг Хятан улсаас буцааж авсныхаа төлөө жил бүр 100 мянган лан мөнгө, торго дурдан өгдөг байжээ. 1070 онд хааны зарлигаар харъяат малчин аймгуудаас жил тутам 300-20000 хүртэл малыг татварт авч байв.

Хятанчууд газар тариалан эрхэлж, гар урлал, торгоны урлал хөгжүүлж, мод чулуун гүүр барьж, бичиг үсгийг улам дэлгэрүүлж, харьцангуй суурьшмал соёл иргэншилтэй байсан учраас замын тэмдэглэл бичиж үлдээжээ. Бөө мөргөлтэй байж байгаад дараа нь бурхны шашин шүтэх болжээ. НТ 920 онд нанхиад үсгийн үлгэрээр хэдэн мянган тэмдэгт бүхий Их бичиг гаргаж, НТ 925 онд 378 үсэгтэй Бага бичгийг зохиожээ. Эдүгээ Хэнтий аймгийн Рашаан хаданд хятан бичээсийн дурсгал бий. Хятанчууд анх удаагаа ном барлан хэвлэж, буддын шашны сургаал Ганжуурыг 5000 дэвтэр хэвлэсэн тухай баримт байдаг. Хятад, солонгос, энэтхэг зохиолуудыг орчуулдаг номын сантай байснаас гадна уран зураг, хөрөг зураг нэлээд хөгжсөн байсныг судлаачид тогтоожээ. Будда, күнзийн сургаалыг дэлгэрүүлж, гадаад орон руу ном судрыг бэлгэнд явуулах, гаднаас ном судар бэлгэнд авч байсан түүхэн баримтууд үлдсэн байна.

Хятаны үеийн олдвор: Хятанчуудын ноёрхол 901-1125 оны хооронд тогтсон бөгөөд монголын нутаг дээр цэргийн цайз бэхлэлтүүд барьсан нь өнөө үед үлдсэн Хэрлэн барс хотын цамхаг, Зүүн Баруун хэрэм, Хар бухын балгас, Чин толгойн балгас зэрэг болно. Эдгээр тууринаас ихэвчлэн хөрөг зураг болон байгалийн сэдэвт зургууд, шаазан ваар, барилгын материалууд олджээ.

Эх сурвалж: Монгол орны лавлах

Та аялал, амралтын талаарх илүү их мэдээ мэдээллийг ЭНД дарж аваарай.

In the chaotic period of destruction and

dispersions that followed the end of the Uyghur Khaganate, the balance of power

now shifted to the so-called “proto-Mongols” far to the east. The Khitan (also

Kitan) were a nomadic people from the eastern end of today’s Mongolia and

Manchuria who’d once been part of the Xianbei confederation in the second

century CE.

When the Wei Dynasty was formed, the Khitan

refused to join their now sedentary cousins and over successive centuries, paid

a heavy price. With their own distinct identity, including a written language,

the Khitan were under constant attack and any attempt to assert their power was

crushed by the Turks to the west and Chinese from south. Even the Koreans from

the east, the Goguryeo, had a go at controlling them.

Under such constant domination and

oppression, any attempts at gaining their own independence were constantly

crushed. Reowned as warriors, the Khitan joined in alliances only to find

themselves betrayed, most dramatically during the Li-shun Rebellion in 696 CE

when the Turkic Khanate encouraged a revolt against the Tang , only to attack

them from the rear, a decisive move for the revival of the Second Khanate. They

suffered further blows from the subsequent cosy alliance between the Uyghur and

the Tang.

The moment for the Khitan finally came with

the routing of the Uyghur in the west and then collapse of the 300-year-ling

Tang Dynasty in the early 10th century. Acting quickly, the Khitan

established the Liao Dynasty in 947 and asserted their power over the northern

China plain. They moved into eastern and central Mongolia, including the

important Orhon Valley, which like others before them became their capital.

Moving west and south, they gained control of the Silk Road and the movement of

salt and iron Diplomatic and commercial relations reached all the way to the

Arab Caliphate and Persia.

Inspired by its contacts with the Chinese,

the Khitan brought another feature to Mongolia’s nomadic society with the

creation of over 150 cities, the ruins of more than a dozen of which are still

visible today, especially in the eastern Herlen River valleys. The most notable

are the ruined walls of twin cities west of Ondorhaan in Hentii aimag. And 100

kilometres (62 miles) northwest of Ulaanbaatar at Chin Tolgoyn Balgas, or

Kedun, in Bulgan aimag are the ruins of a significant fortress that include a

stupa believed to be one of the oldest Buddhist monuments in Mongolia. These

Khitan cities were religious, commercial and agricultural centres, including

the cultivation of silk. Its military power weakened the tradition of tribal

confederations with the empire divided into two parts, one based on nomadic

traditions and the other on the Chinese model.

Fearful of losing their hard-won ethnic

identity, the Khitan fiercely maintained their own traditions, refusing to use

the Chinese language. They devised their own writing system, which is still

difficult to decipher. Buddhism became the state religion but, as always in

nomadic society- including the Mongol Empire- they accepted other sedentary

religious, most importantly Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity.

Confucianism and Taoism also became part of the Khitan culture. Today’s

Mongolian culture was heavily influenced by the Khitan.

While their empire lasted over 200 years,

internal struggles around 1125 led to their conquest by Jurchen, a pastoral and

hunting tribe of Tunjusic background and ancestors of the Manchu from the far

north of Manchuria, who established the Jin Dynasty. While some stayed on to

help fight the southern Song Empire, some 100,000 Khitan, including its

leaders, migrated westwards through the Altai Mountains where they established

the sizable Kara Khitai Khanate, or Westren Liao, in Central Asia. Still living

as nomads, they conquered the mostly sedentary Muslim tribes of the region,

turning their mosques into Buddhist or Nestorian Christian churches. When word

of Kara Khitan leader Gur Khan’s deeds reached Rome, who’d just lost control of

Jerusalem to the Muslims, this gave rise to the legend of Prester John and a

savior of Christianity from the east.

From their capital at Balasagun in today ‘s

Kyrgyzstan, they ruled for nearly 100 years before the Empire’s diversity of

tribes led to rebellion. When Genghis Khan moved on the Naimans, a powerful

Turkic tribe then controlling western Mongolia, many fled to the khanate,

briefly usurping power there before Kara Khitai’s final destruction by the

Mongol Empire in 1218. Interestingly, considering their dispersal and virtual

disappearance from history, the Khitan’s name survives in today’s words for

China and Russian (“Kitay”), and the classic English “Cathay”, Portuguese

“Catai” and Spanish “Catay”.

With the Jurchen preoccupied as they extended

their power over eastern China and korea as the Jin Dynasty, the steppes of the

Mongolian heartland returned to a state of disorganized nomadic tribes in an

almost constant state of war. But they also faced threats from more organized

outsiders. They feared not only what the Jurchens might do next, but the Song

Chinese Dynasty south of the Yangtze River and the Tangut Khanate, a

Tibetan-related people controlling western China as the Western Xia

(1038-1227.) With five or six tribal confederations vying for power and

influence, this way the situation inside Mongolia at the end of the 12th

century.

Resource: Carl Robinson "Mongolia Nomad Empire of Eternal Blue Sky"